The Zero-to-Vibe Coding Jumpstart Cube Catastrophication

From Pauper to Pandemonium: Building a Magic Jumpstart cube when you can’t change anything

The Problem: Jumpstarting a Pauper Cube

This story starts, as with all good stories, with a bad idea that just wouldn’t get out of my head.

I hadn’t played Magic: The Gathering in 20 years, but the idea of building a Pauper Jumpstart Cube was too enticing to ignore. It all started when I came across this Reddit post that described how trading card games like Magic could be treated as curated board game experiences. That led me to discover thepaupercube.com, and I was captivated.

For the uninitiated:

- Magic: The Gathering is a collectible card game that mixes strategy, fantasy, and an unholy amount of rules.

- Pauper format only allows commons, the lowest rarity of card. It’s great for design constraints and budget builds.

- Jumpstart is a format where you mash two themed 20-card packs together for instant deck-building fun.

But there was a snag: where do I even get these cards?

At first, I tried buying them — until I saw the price. About £250 for the cards and an eye-watering £500 for shipping. Absolutely not.

Eventually I figured out how to print proxies using MakePlayingCards.com and sourcing the images and data from mpcfill.com. This workaround gave me control, affordability, and the ability to experiment freely.

Now I had a freshly printed Pauper cube in hand… and absolutely no idea what to do with it.

That’s when I came across Hasted’s Cube on CubeCobra — a Jumpstart cube built from a Pauper cube. It was basically perfect. Everything I wanted! The archetypes were there, the card synergy was elegant, the deck themes were fully formed. Instant salvation!

Except… there was a problem.

Hasted’s cube was built in September 2024. My version of the Pauper cube — freshly downloaded and printed — was from June 2025. As I soon discovered, the Pauper Cube is a community-maintained project that’s been actively updated every three months since 2008.

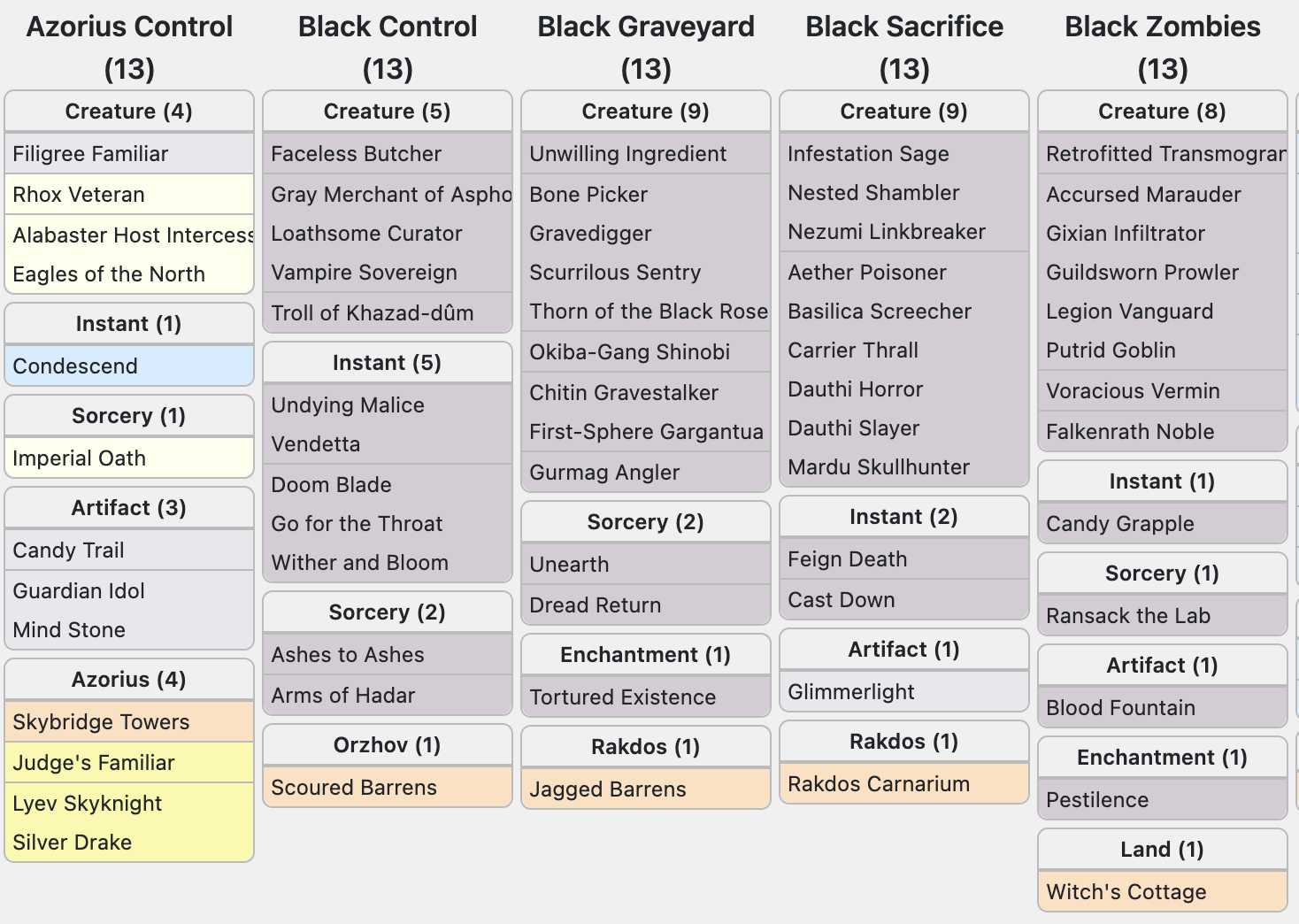

So I was 3–4 patches ahead of Hasted. Many of the cards his cube used had been removed or swapped out. When I tried to rebuild or expand his design, I quickly realized I was missing about 30 cards. Only 260 of the 450 cards in my cube were being used, and the 10 dual-color archetypes from his Jumpstart structure? Gone.

My brilliant idea? Build the Hasted decks as-is, then look at the leftover cards and do my best to patch in replacements that matched the original themes.

Which, given I hadn’t touched Magic in 20 years, turned out to be far harder than I expected — I barely understood what the cards did, let alone how they synergized.

Smooth sailing? Nope.

Wrong. Welcome to cube catastrophication.

The Solution(s): Iterating Toward Sanity

🛠️ Step 1: Do It By Hand

My first instinct was to patch in the decks manually. I started with Hasted’s archetypes and filled in gaps using leftover cards, trying to match themes as best as I could. It took hours. By the end, I had something that looked playable — but I had zero trust in it. Colors kind of matched, synergies sort of existed, and I kept second-guessing every choice. These were artisanal, hand-crafted, duct-taped abominations. They technically worked, but just how good (or bad) were they? I had no idea.

🤖 Step 2: Enter ChatGPT

Clearly it was time to bring out the big guns. AI to the rescue! It would magically do everything I wanted, right?

So I chucked a CSV with a list of cards, Oracle text, and some additional metadata at ChatGPT, along with — in hindsight — an absurdly naive prompt:

I am considering making a jumpstart cube from a pauper cube (see attached file). I need themes for the decks given the pauper cube. Could you generate 20 mono-colour themes (4 of each colour) and 10 dual-colour themes? Could you also include a list of potential cards that would fit that theme given the cube list attached?

What could go wrong?

At first glance, it was perfect. It generated a whole bunch of themed decks and cards to go with each one. It looked amazing.

But… it didn’t take constraints into account — like the fact that each card only appears once in the cube. Or that many of the cards it selected didn’t even exist in the list I had provided.

I found myself going back and forth, trying to mangle the data into a structure that was vaguely plausible. But eventually, I just got lost. The AI was enthusiastic, but this wasn’t working.

🧠 Step 3: Better Prompts

It was becoming increasingly obvious that the prompt I had started with just wasn’t working out. So I spent time hand-crafting a new one. (In hindsight, I probably should’ve asked GPT to help write the prompt — but that idea came much later.)

The new prompt:

Hi, you are a deck designer working on building game decks in Magic: The Gathering focusing on Jumpstart decks. You need to build a set of decks from a Pauper cube (see list of cards available in attached file).

Your goal is to create 20 mono-color decks (4 of each type) and 10 dual-color decks. Each deck should follow the rules of Jumpstart deck construction.

Let’s start with creating themes for each of these decks and assigning some cards to match those themes. Key constraint is that we cannot assign a card more than once from the Pauper cube list as they are uniques.

CONSTRAINTS:

- You may only use a card once across all 30 decks

- You may only use cards that are in the list of cards provided

- You must ensure that the decks you construct are valid; cards in each deck should be usable with mana from that deck

- You must ensure the chosen cards match the themes you have defined

This time, I had a clearly defined role, concrete constraints, and structured tasks.

This was it — the magical incantation that would solve all my problems…

Nope.

It struggled to generate valid cubes. It kept reusing cards. Decks were sometimes the wrong size. And worst of all, the data lived entirely inside GPT’s reply: in a format that was hard to verify or visualize.

I had to keep going back and forth to fix errors, find inconsistencies, and validate logic. Eventually, the prompt-response loop collapsed under its own weight. I ran out of context window, and the outputs started to degrade into nonsense.

🧠✨ Step 4: Better Model, Same Problems

Okay, so maybe the prompt wasn’t the problem. It was clearly much better than the first one. Maybe the real issue was the model I was using.

I had initially been working with GPT-4o, but I decided to switch to GPT-4-turbo (o3). And oh my word — the reasoning was incredible. Reams of Python code, clearly explained logic, thoughtful breakdowns. This was it. This was going to work!

…Nope.

Despite the improved explanations and structure, I ran into the same validation problems. Constraints were still being willfully violated. Cards were duplicated. CSVs had to be regenerated and re-debugged over and over and over again.

There was just too much context needing to go over the wire. Too much reliance on remote execution and ephemeral chat memory. I had no local reproducibility, no way to rerun anything myself — and too much of the process was invisible, buried in model responses I couldn’t reliably audit.

This was not working.

📓 Step 5: IPython Notebooks with Claude

I had recently been playing with agentic programming in IPython notebooks and thought to myself, “Hey! An IPython notebook might just be the ticket!”

So I set up a repo with a notebook and used GitHub Copilot along with Claude 4 Sonnet, treating it exactly the same way I’d treated ChatGPT: start with a prompt, feed in some context data, and ask questions.

Claude wrote all the Python code in the IPython notebook, and I could rerun things. This was great — I now had the data locally. I could iterate. I could export everything to a CSV in a format compatible with CubeCobra. I was finally developing a working validation process.

It was really working!

Until… it wasn’t.

Rapidly, the notebook exploded to over 10,000 lines of Python and Markdown. It became completely impossible to understand. I was noised out. There was too much code, too many hidden assumptions, and I couldn’t maintain any meaningful context anymore.

💫 Step 6: Vibe Coding

There’s a saying: when all you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. I’ve been coding since 2000 — I should have known better.

Just getting the AI to dump everything into a single file and hoping for some semblance of sanity clearly wasn’t working. So, I decided to try vibe coding consciously for the first time. I started writing reusable functions: one to export CSVs in a consistent format, another to validate that cubes were generated correctly, more to parse the data and swap cards in and out.

Bit by bit, a new structure emerged: a collection of a dozen files, each with around a thousand lines of code. It was big, messy… and actually working.

I uploaded a CSV to Cube Cobra — and it was starting to look right. Not perfect, of course — there were still bugs. But these were bugs I could work with.

Encouraged, I kept going. I asked more questions. Tweaked more things. And then I hit that familiar point in every real-world software project when you skip refactoring. Everything becomes chaotic, fragile, and painful.

Some files grew so massive they defied comprehension. I had hit cognitive overload again. I couldn’t understand what I was reading anymore.

As an ardent TDD advocate in my day job, I realized I was missing two critical pieces of the red-green-refactor cycle: I was just writing code. No tests. No cleanups. Rookie mistake.

🔁 Step 7: Start from Scratch, Methodically

I decided to start from scratch, taking a leaf from Code Retreats and embracing the idea of throwing away code. I began with creating clean modules to construct a deck, refactored out constant values, and organized logic around key ideas. I added the ability to balance decks using different metrics, gave themes the ability to value cards differently, and even got the AI to extract themes from all existing Magic cards and map them against the cards I had available.

This time, I embraced a conscious build-and-refactor loop, following many of the patterns and code-smell habits Uncle Bob Martin drilled into me back when I first read his books. Slowly, things started to click. I had a system that could take a list of cards and — hands-free — generate a Jumpstart cube that actually worked.

And it was beautiful. The decks looked reasonable (at least to my untrained eye), and they respected the constraints of working within a limited cube.

The experience of vibe coding here was totally eye-opening. It required a different mindset — more like pairing with a junior engineer. There was back-and-forth about design patterns, code smells, duplication, and testing. It was a collaborative, iterative process, not what I had anticipated at all when I set out to “just get the AI to do it for me.”

Learnings

I came away from this with a set of learnings I didn’t anticipate. Over the course of this project, I used a wide range of AI tools — ChatGPT, Claude, GitHub Copilot — not just as assistants but as creative collaborators. The work would’ve been infeasible to complete by hand; AI didn’t just make it possible, it changed how I approached the problem.

AI is a Force Multiplier — With Strings Attached

- AI made exploration and iteration possible at speeds that felt impossible before.

- But it was only effective once I provided structure: clear prompts, reusable functions, validations, and constraints.

- It was never “write this for me”; it was “pair with me while I figure this out.”

ChatGPT

- Great for brainstorming, naming, structure, and kicking off ideas.

- Struggles with long-running logic or deeply stateful tasks.

- Context limits are real — and painful. Once you hit them, coherence breaks.

- Loves to generate Python, but not always consistently or responsibly.

Claude + IPython

- Being able to run, re-run, and inspect code locally was a game changer.

- Having longer context helped — until the notebook turned into a 10k-line mess.

- Still, this was my turning point: the shift from “AI as magic” to “AI as collaborator.”

Vibe Coding

- Treating the AI like a junior engineer was the breakthrough.

- I focused on function-level design, modularity, and code smells — and the AI followed along.

- Once the codebase was structured, the AI stopped hallucinating and started contributing meaningfully.

- But skipping testing and refactoring led me right back into chaos. The rules of clean code still apply.

The Meta-Learning

- The process changed how I think about coding, prompting, and problem-solving.

- It wasn’t the model, or the prompt — it was the interaction between human intent and machine output.

- I didn’t just build a cube. I learned how to build with AI — iteratively, imperfectly, and eventually successfully.

The GitHub Repo

Want to see the madness? The final codebase — notebooks, card lists, helpers, and all — is here:

👉 github.com/vanonselenp/magic-jumpstart

👉 Cube Cobra: The actual cube generated

Final Thoughts

This project started as a light-hearted return to Magic and spiraled into a lesson in prompt engineering, AI pair programming, and the perils of working with 13k-word datasets inside stateless chat threads.

Would I do it again?

Absolutely. But next time I’ll write the tests first.